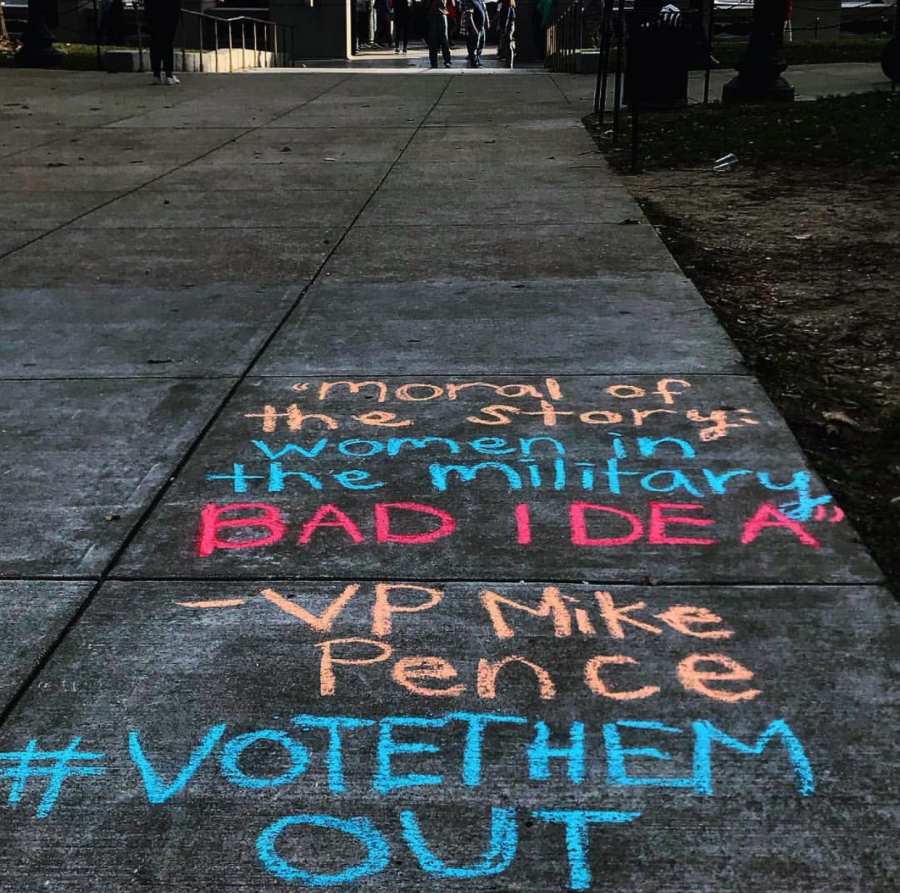

Cat Calls of NYC

December 4, 2018

The sky is clear, the day is warm, and you’re wearing your new pair of boots for a stroll out on the town. You’re smiling, enjoying the day, as you walk along the streets of your city, when all of a sudden, a rough masculine voice calls out, “Mm, baby, you should get down on your knees!” It came from a middle-aged construction worker across the street, who is now making vulgar gestures and ogling you. Can you imagine how you would feel?

Emma Petersen (12) can. “[The Poms team girls] were taking team pictures outside and some guy yelled out his car window, ‘I want to impregnate you all!’” said Petersen of her catcalling experience. “The overt objectification from the catcall was belittling to us- as [the catcaller] obviously saw us as things to be used and discarded- and it was honestly quite scary… I couldn’t do anything about it because none of us knew him and he drove away. We felt powerless in that situation.”

According to Merriam-Webster, catcalling is defined as “to make a whistle, shout, or comment of a sexual nature to a woman passing by.” Women everywhere in the world face this sexual harassment on streets, on trains, in workplaces, despite the laws in place against catcalling. One of Colorado’s statutes classifies stalking and making seriously annoying and uncomfortable comments as harassment, and many other states have laws against catcalling, however the effectiveness of these laws are called into question when catcalling is still as commonplace as it is.

But luckily for Petersen, she doesn’t have to feel alone in her experience.

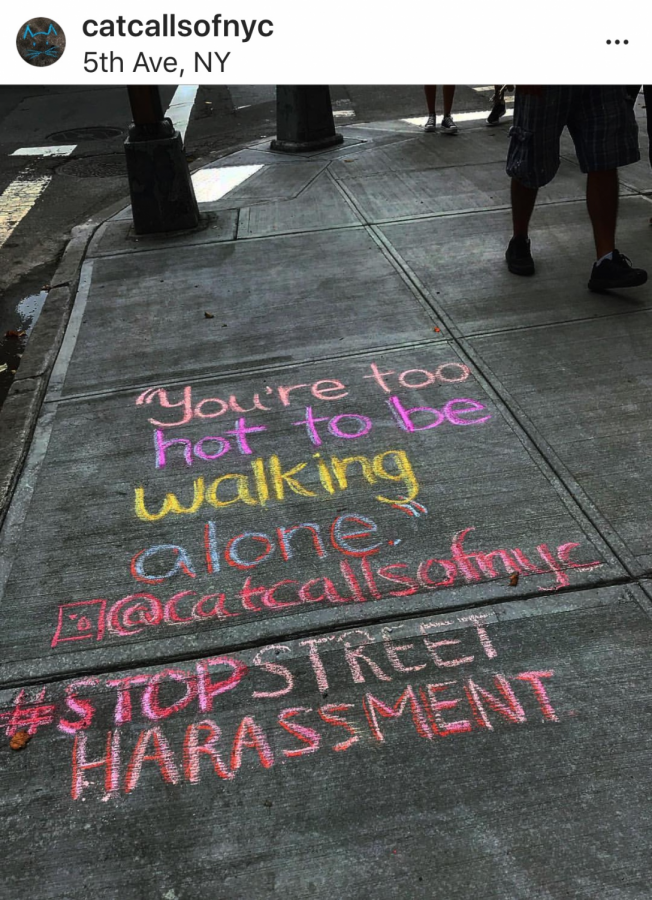

#CatCallsofNYC, an account created by artist Sophie Sandberg, uses her talent to make a difference in New York, where street harassment against women is common, too common. To leave her mark, Sandberg simply takes colored chalk and writes the nasty comment at the place the harassed girl was verbally assaulted. Such an uncomplicated move but with such an amazingly positive outcome. “I’ve collected hundreds of stories about harassment in NYC, so it’s really allowed me to become an expert on catcalling and understand some of the underlying attitudes behind gender-based harassment,” Sandberg said of the impact her project has had on her life and others around her. “This project has given me so many opportunities. Running this project for the past two and a half years has given me a lot of insight on gender-based harassment.”

Not only has Sandberg’s artistry made an impact in New York City, her movement has spread to London, the United Kingdom, Amsterdam, Sydney, and dozens of other places around the globe. There are @catcallsof__ accounts popping up all over the globe, all started by this creative and empowering idea of Sandberg’s.

“I feel sad and angry when I get messages about the harassment women have faced. It’s so hard to hear these disgusting stories over and over again. However, it feels good to be able to give them a space to share and hopefully make them feel supported,” Sandberg said. Her Instagram account where she showcases the drawings of the catcalling comments has over thirty-two thousand followers and her work has gotten her a platform to share her voice. “I started Catcalls of NYC for a class project my first year of college… and I’ve gotten international press attention on the project. I’ve been able to speak about the project, and catcalling, on the radio and on live TV. I’ve been invited to speak at an all-girls’ middle school about the project,” Sandberg said.

Catcalling arguably causes mental damage that can extend beyond what can be diagnosed by a doctor. Through experiences like Petersen’s, girls often change their clothes, how they act, what they say, when they go out at night, just to say safe in a society that has not been protecting them.

“I just think about what not to buy, like slutty stuff or things that could be thought of as slutty,” said Madi DeVries (10). DeVries was catcalled by a guy her age, leaving her scared to walk through the hallways. “It kind of diminished my confidence since I don’t want someone to judge me in a negative way based on what I wore in that one moment.”

And with the ineffectiveness of the laws and the perpetual cycle of harassment, who’s to say that catcalling will become legally and socially outlawed any time soon? There’s much to said about how catcalling can be stopped in our community.

“I don’t truly think we’ll ever be able to get rid of catcalling. It’s a maturity thing. But I do think that we can improve as a society if we are better informed about the impact of our actions on others,” Petersen said. “As a member of Student Action Task Force, this is one of our main goals.”

DeVries says, “Just people knowing about it isn’t enough to have people stop. I think it happens because guys can be open about what they like to see as weird as it is.”

So the real question boils down to how each individual can make a difference in the fight against catcalling.

“It’s so important that if you’re a young person facing harassment that you talk about it. Talk with someone you trust, friends or family, a teacher at school, and tell them what’s happened and how it made you feel. Too often, adults belittle harassment,” Sandberg said of the experiences she has been asked to draw, as well as her own experience being harrassed. “Since I dealt with catcalling growing up, I’ve been able to find a productive way to fight back against it. I’m going to continue to raise awareness about street harassment and other forms of harassment.”